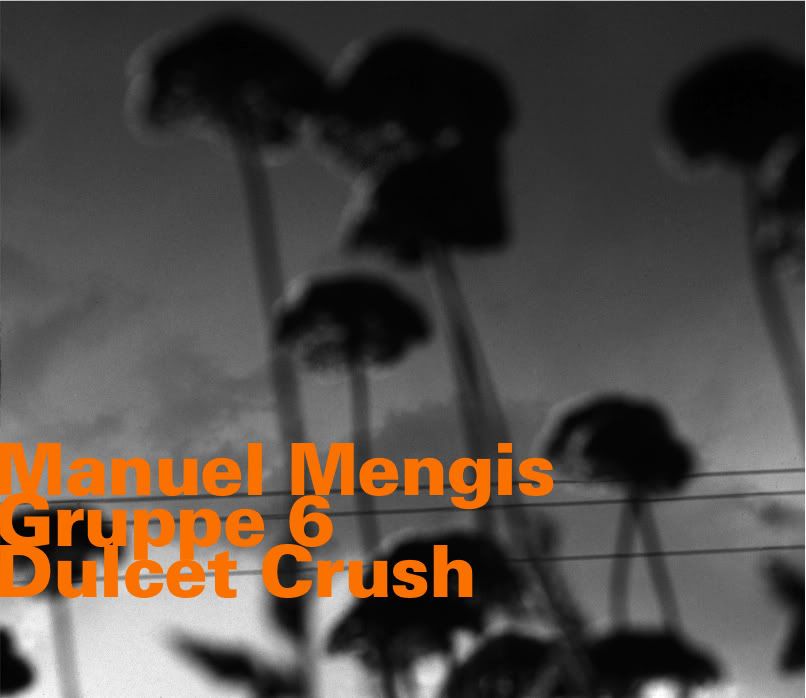

HatHut Records / Hatology 684

HatHut Records / Hatology 684

Release: October/November 2009

Manuel Mengis – trumpet

Reto Suhner – alto saxophone, alto clarinet

Roland von Flue – tenor saxophone, bass clarinet

Flo Stoffner – electric guitar

Marcel Stalder – electric bass

Lionel Friedli – drums

1. Plant Life

2. End Of A Record Breaker

3. Bling Bling Cowboy

4. Luscious Delirium

5. Sustain The Gain

6. The Opposite Of Spring

7. How Mario Tut Tut Got Super Wow Wow

8. We Come In Peace

[ Total Time: 52:02 ]

All compositions by Manuel Mengis.

Liner notes by Frederick Bernas.

Back Cover

Is three the magic number? For many jazz musicians it’s an important one. Every record is of course significant, but the third is often more closely scrutinised. In this sense, it’s both a great opportunity and a niggling pressure: the chance to really begin cementing a good name, with a little weight of added expectation.

Manuel Mengis, however, did not feel any of this. He even identifies a more relaxed approach than his two previous releases, partially due to shifting priorities in life. An atmosphere of light, easy contentment shines through the music – Mengis and the Gruppe 6 are really enjoying themselves, free of any kind of external strain. And the pleasure is contagious.

Liner Notes: Small Town, Big View

April 2009

“Jazz is the world’s most decadent form of music!” growled my soft-rock loving lawyer flatmate in a typical coarse disposition. When I received the rough tracks for Manuel Mengis’s new record, I don’t think my neighbours in Moscow knew quite what had hit them. To my friend, a guy who’d been to only one jazz gig in his entire life, Dulcet Crush would have seemed as alien as – well – European contemporary jazz to an avid pop fan.

But Mengis identifies a marked change of approach in this, his third album, compared with two previous releases on HatHut: “I think this album is easier to follow. I try to make music that can also touch people not into the jazz scene, at least when played live.”

A glance down the track list shows something of a radical departure. Whereas Into The Barn and The Pond featured four tunes apiece, we now have double that. All but gone are the 15-minute epic explorations. A clear spirit of simplicity was at the heart of Mengis’s concept, but he believes it represented more a natural evolution of his compositional style than a conscious, deliberate decision. “I had lines in my head that were easy to sing along, really logical melodies one can remember.”

“This time I tried to stay more with one idea or one atmosphere in a piece – not trying to tell the full story within one piece, but through the whole record. I don’t want to make the music more special than it is. In fact, I really wanted to keep it quite easy at times. Some parts sound like they’re written for a crooner, pathetic to the limit; other times it sounds like Hollywood, the ‘Rocky’ boxing movie, or very pop. I also use clichés, but I like them because they take the music down to very clear images, part of a common memory. They can still express authentic feelings.”

“Some melodies are maybe naïve, but I like to check the limits and try to stop before they turn into bad taste, banality or trite. They are also used as a sort of counterpoint to weirder, more abstract spots.”

When we talked in late 2008, for an interview published on AllAboutJazz.com, the trumpeter spoke in detail about his writing methods. “I have a lot of different ideas in my mind. In the first few days, I need to find out what I really want – which notes I want to use. I write a lot of stuff, throw some away, edit, and then after a few days I’m really into it – I can get a clearer picture.”

Things happened differently for Dulcet Crush: “I changed my way of working. I did a lot in my head, turning things around and trying to get rid of unnecessary parts in advance, before I started writing things down. A lot of pieces were finished much faster. I’m changing my processes.”

So what led to this subtle shift in his creative dialectic? “I think I am getting more trust in my writing and meaning, and the band and the sound we make. Maybe somehow it becomes less ambitious, but I don’t know if that’s the right word. I am getting more clear and relaxed in how I work, becoming more comfortable with myself. Also, I think looking after two children and reconstructing an old house had some influence; I was forced to work more efficiently and maybe not take my music too seriously.”

Mengis also believes the Gruppe 6 is really growing into its own musical organism, contributing considerably to that crucial trust factor. “I think we have found our own sound, which means it’s not necessary to construct everything anymore. Everybody has reached a point where they know what I mean; I was more focusing on how things were played than what was going to be played.”

Drummer Lionel Friedli agrees there is copious mutual understanding within the group. “The studio vibes were really good, the energy between us was very strong. We have a lot of experience playing together, so I think that has created a very natural feeling and a lot of joy.”

Friedli credits the bandleader with fostering this open, fertile collective mentality. “Manuel knows exactly what he wants, but he also knows when to simply let it go, let people take their place and put their own ideas into the music. He has a good balance between the two sides.” This is aptly demonstrated on tracks such as ‘Sustain the Gain’ and ‘End of a Record Breaker,’ which combine strictly prescribed written passages with swirling, tempestuous improvisations that express an electrifying unspoken chemistry.

Mengis emphatically paints a variety of moods in vivid colours, from “tiny, peaceful” lullabies to anarcho-funkadelic “hero music” freak-out with echoes of John Zorn’s Naked City. It’s a study of extremes, but nonetheless a consistent effort. A clear individual touch unifies this set of highly differing compositions, partially due to a couple of sneaky recurring themes worked into the charts. “There are little connections,” Mengis explains. “Melodies here and there will occur more than once; I was thinking about the whole record. For example, just before the end of ‘Plant Life’ we have quite a prominent theme, which comes again on ‘We Come in Peace’. It’s like a memory of the other tune.”

“Critics have compared our records to various other people, but I don’t know,” muses Friedli. “There are some complicated themes that can make connections to the contemporary avant garde, but it’s very personal music to me. Somewhere it can sound maybe like pop, but the instrumentation is also distinct. Manuel makes his own authentic sound, he has his own universe.”

In this private cosmos, Mengis is not afraid of unorthodox experiments. “On a few tunes I made some kind of background noise with things lying around at home. I have an old kalimba my sister gave me, and I actually never played it. But I wanted to create some additional atmospheres in the background, so I was playing around with that kalimba, a toy piano and bells at the session. I also had an old cittern at my father’s place, from my grandfather – some noises you hear on ‘How Mario Tut Tut Got Super Wow Wow’ are made by that. It’s nothing really new for this type of music, but that was no reason not to try myself.”

“I have no clue how to play the cittern properly, but maybe I got inspired by the light-heartedness of my children, which I’m so glad for. Of course I had to be careful, I didn’t want to push it too far. There’s a border: it can quickly become phoney, but that doesn’t matter to me because it was a really spontaneous thing to try. I was fooling around with those little toys, and in some ways that kind of attitude is important for everyone who plays on the record. For example, Flo Stoffner uses a lot of different sounds and is full of surprises – just like the rest of the band.”

A fortuitous countryside encounter gave Mengis, who lives in the mountainous region of Switzerland, another flash of inspiration. “One little idea came from a time I was coming down from the mountains. There were some goats crossing – like 50 of them – suddenly all around me, hoping to get some food; a few tried to eat my clothes. I took out my mobile phone and recorded the goats’ bells to make a new ringtone. And that’s what you can hear on ‘The Opposite of Spring;’ I left the ringtone in there, holding my phone to the mic. It has two sides: a really romantic element, being in nature, but also the cheap sound quality of a mobile phone. That gives it a kind of strange junk aspect I wanted too.”

The creative dynamics of small-town life have also affected Mengis, who “cannot hide within a circle of other musicians.” To me the phenomenon seems almost like semi-brutal self-exposition. “The only chance I have to make myself understood as a musician is to create my own stuff,” he explains. “I can’t just go around town every night, meet other musicians and everybody helps each other out. When you are out of that kind of environment, you maybe have to answer certain questions differently.”

“The place where I live, my work as a mountain guide – all that may seem a little exotic. But does it make my sound different? I mean, almost every jazz musician has another job on the side. And sure, when you don’t live in a cultural centre, it takes extra effort to know what’s going on and be inspired by the work of others. But everyone is trying to do their own thing – in Berlin, New York, the countryside or wherever.”

“Sometimes you feel isolated, but I am lucky to have a good label, people who support my work and, most importantly, friends in the band,” states Mengis. “I am happy. We are at the point where everyone is ready to surf the music.”

An individual musical universe can develop anywhere. In the words of Friedli, Dulcet Crush is “a kaleidoscopic view on the mind of Manuel.” Welcome to the panorama.

Currently living in Russia, Frederick Bernas writes about music, politics and culture and needs more time to play his tenor saxophone.