As dusk falls in the Elqui Valley, a packed minivan rumbles up a winding trail into the hills, high above the gleaming orange lights of Vicuña – a small town at the heart of Chile’s recent boom in astro-tourism.

After 40 minutes on the dusty road, lined with scrawny bushes, cacti and rocks, the van arrives at Pangue Observatory. Opened in 2008, it’s one of about a dozen tourist observatories scattered around Chile’s northern regions, which have some of the clearest skies in the world.

After 40 minutes on the dusty road, lined with scrawny bushes, cacti and rocks, the van arrives at Pangue Observatory. Opened in 2008, it’s one of about a dozen tourist observatories scattered around Chile’s northern regions, which have some of the clearest skies in the world.

“I used to go on ‘astronomic safaris’ with my Canadian friends. We would take a telescope, drive into the valley and observe all night long, so I knew foreign visitors were interested,” says Cristian Valenzuela, one of Pangue’s two founders.

The other is Eric Escalera, a professional astronomer who left his native France six years ago. “Over there, tours are impossible,” he says. “It’s a disaster with all the clouds and climate problems.”

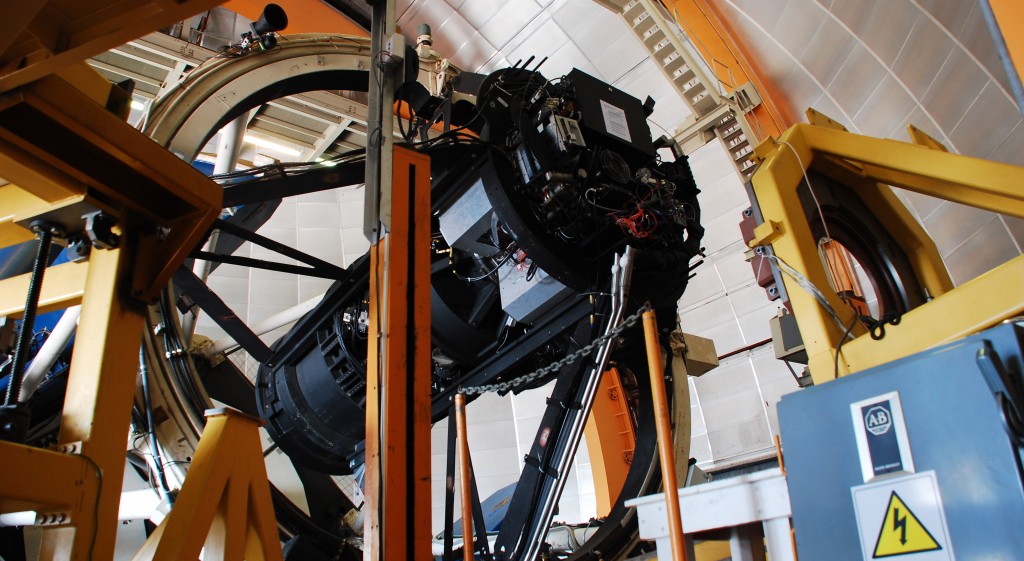

Pangue offers stargazing sessions with a $45,000 telescope that range from three hours to a whole night. The largest group size is 15 and programs are designed for enthusiasts who know more than your average tourist.

Across the valley, hundreds of visitors per night flock to the municipal observatory at Cerro Mamalluca, which opened to the public in November 1998 as the first project of its kind.

“Back then, it was just an experiment – our first tour had two people,” says guide Luis Traslaviña, as the observatory’s spherical roof slides open to reveal a vast panorama of planets, constellations, galaxies and the occasional shooting star.

“I’ve worked here for 16 years, and there’s never been a day when nobody came.”

Although many newer observatories have sprung up, Mamalluca’s popularity is not wavering: Last year, it welcomed more than 45,000 of the region’s 150,000 visitors.

The telescope was donated by Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a nearby scientific complex that houses the world’s largest camera.

Every weekend, Tololo’s doors open to visitors who marvel at the huge 570-megapixel instrument used to study dark energy and the expansion of the universe.

A series of even more ambitious projects is coming to Chile in the next few years. The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), a camera boasting 3,200 megapixels, will catalog the entire visible sky and publish images online – allowing anyone with a computer to zoom through space and potentially make discoveries.

The Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) and the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) will bring more groundbreaking technology and global prestige.

And Chile already has the $1-billion ALMA radio telescope, an array of 66 antennae in the Atacama Desert that probes the cosmic origins of life.

By 2020, the government estimates it will host 70 percent of the world’s astronomical infrastructure.

As tourists are sure to continue following the scientists, entrepreneurs have been finding creative ways to capitalize.

Elqui Domos is a hotel designed with the stars in mind. Dome-shaped rooms feature removable ceilings that open onto the sky, and observatory cabins with glass roofs are also available.

Many more hotels provide telescopes for guests to use, but Alfa Aldea hostel recently built a small amphitheater in the middle of a vineyard.

During nightly tours, wine, snacks and blankets are handed out while a guide talks about space history. Groups then get a chance to see more with telescopes.

“It’s a family experience – I like that children are encouraged to participate,” said Maria Celeste Valenzuela, a teacher from Santiago. “The best thing was looking at the sky, sheltered by your blanket, surrounded by nature and listening to the sound of crickets.”

But tourism also brings development and the danger of light pollution. The neighboring beach towns of La Serena and Coquimbo, about an hour away from the Elqui Valley, are growing rapidly; the IV region’s population has swelled to over 700,000, adding more than 200,000 people in the last 20 years. Mining is another boom industry.

Anticipating this risk, in 1999 the government issued a decree to regulate light emissions across northern Chile. Provisions include power limits for public lighting and that street lamps are shielded to face away from the sky. Last year, new rules were added to cover neon signs, billboards and LED or plasma screens, along with stricter guidelines for sport and recreational facilities.

Chile is also working with a group of astronomers in lobbying UNESCO to add major astronomy sites to its World Heritage List. The aim is to establish a link between Science and Culture – the S and C in UNESCO – to preserve locations connected with studying the history of mankind.

Several “Windows to the Universe,” including the Coquimbo region, have been identified – along with four categories of astronomical heritage.

“When I first arrived in La Serena, in 1969, I could see the Milky Way from the town square,” says Dr Malcolm Smith, an astronomer involved in the UNESCO initiative. Today it is no longer visible.

“Protecting the future is awfully hard, and they have changed a lot,” Smith continues, “but there is still more to do. Chile has to make these decisions for itself.”

Published @ BBC.com, 24/4/14 – click here for original.