Writer & Photographer: Frederick Bernas

For one night in November, the famous obelisk in downtown Buenos Aires was bathed in pastel colors, rippling in tandem with a catchy electro-folk soundtrack played by musicians below. The slogan “Wine Unites Us” flashed above a curious crowd, while renowned Argentine graffiti artist Milo Lockett sketched quirky designs depicting wine in all its manifestations, from grape to glass.

The event marked Argentina’s National Day of Wine, but the country’s industry has recently had little cause for celebration. A slump in consumption, poor harvests, rising prices, and a host of structural and economic issues form a perfect storm for producers of the Argentine national beverage.

“The world has changed, and it will keep changing,” said Sergio Villanueva, general manager of Argentina’s Viticulture Union, and one of the brains behind the obelisk culture jam. “We need to work on winning back the mentality of consumers by reminding people that wine is part of our DNA.”

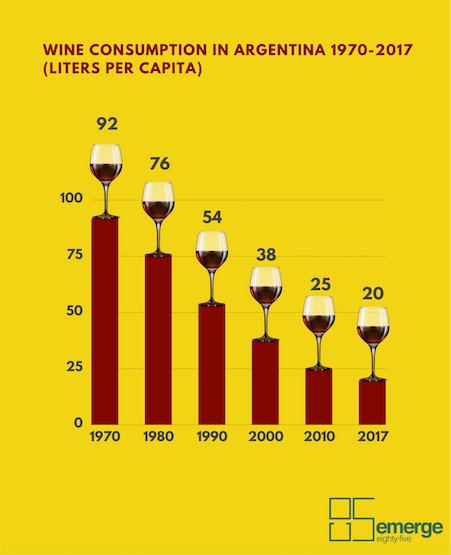

From a remarkable high point of 92 liters per capita in 1970, wine consumption in Argentina has collapsed over subsequent decades: 76 liters in 1980, 54 in 1990, 38 in 2000, and just 25 in 2010. In 2017, it fell to 20 liters for the first time, exacerbated by two of the worst harvests in half a century as rain and pests ravaged vineyards in the fertile Mendoza region, where 70% of production takes place.

That shortage led to soaring grape costs, which in turn caused retail prices to rise above the rate of inflation, burning consumers at a time when purse strings were already being tightened across the country due to an economic downturn. Combined with a craze for craft beer in cities like Buenos Aires, the wine industry is facing a toxic mix of seasonal and structural woes. But redemption could come in the form of exports.

For Argentina to compete globally, the country’s wine producers must look to other emerging markets with a growing thirst for wine, such as China. Although declining local consumption speaks to the depressed state of the national economy, the country’s wines are highly rated and have the potential to be a strong export commodity. But government mismanagement and the volatile weather that occasionally threatens wine regions are major challenges for the industry in its quest to bolster export levels.

France has cheese, Argentina has wine

Wine has been cultivated around Mendoza since the mid-16th century, but it took another 200 years for the grape that made Argentina’s name to arrive in the region: Malbec. In 1853, influential intellectual Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (who later become president) founded a viticulture institute and hired Michel Pouget, a French agronomist, to run the operation. He was assigned to import the finest vines from his homeland – Merlot, Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon – and work out which varieties adapted best to local conditions.

At the end of the 19th century, as European migrants flowed into Argentina, the culture of drinking wine firmly took root in the national psyche. The Sottano family of Italian vintners were part of that wave: Fresh off the boat in the late 1800s, they acquired a farm near Mendoza and started cultivating, aided by knowledge gathered over generations. Their story is a parable of Argentina’s wine sector over the last 130 years.

“Until 1940, my grandparents had one of the most important bodegas [winemakers] in the domestic market,” explained Federico Sottano. But the family business collapsed as consumption began shrinking in the 1970s and 80s. In response, wine producers shifted their business model from high-quantity production to high quality in lower quantities.

Economic trends help and then hurt the wine sector

Although Argentina’s calamitous 2001 debt default spawned political chaos, the resulting peso devaluation created favorable circumstances for export, helped by the emergence of Malbec as a sought-after wine.

“The industry grew at highly elevated rates between 2001 and 2010,” said Javier Merino, an economist who specializes in the wine sector. “But then macroeconomic deterioration began, so Argentina started having a fiscal deficit again.” He explained that the populist governments of Nestor Kirchner (2003-07) and his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (2007-15), raised public spending “to cover up a lack of growth in the private economy,” as well as introducing tax hikes to match.

“Higher taxes, higher inflation, and an exchange rate that didn’t follow inflation was a really bad combination for wine exports,” Merino continued, sipping a coffee on the terrace of Mendoza’s Park Hyatt hotel. “Today, the profitability of Argentine wineries is about a third or below of the global average, whereas until 2010 they exceeded it. That also means producers are cutting investment in their infrastructure.”

Wine is replaced by beer and soft drinks

It falls to industry associations to try and unite the frequently competing interests of winemaking firms, which do not necessarily play as a team on issues such as price regulation and marketing strategy. “We need to get everybody around the table with a map, like a grand state at war,” said Sergio Villanueva of the Viticulture Union. His foes are rival segments of the beverage sector, namely beer and soft drinks, which have been carving out a bigger share of the Argentine market as wine consumption has plunged.

Going into battle against Goliaths like Pepsi, Coke, Ambev, and Danone is an uphill struggle for the winemakers. But Villanueva and his allies believe the culture war can be won with Argentina’s strong wine tradition, no matter how many celebrity ad campaigns the megacorps buy. “Coca-Cola and beer go all over the world, but wine has more identity. It’s different everywhere,” said Villanueva. “There aren’t many products that carry so much pride in Argentina.”

“We are companies with a human dimension,” added Jose Alberto Zuccardi, the owner of a major bodega that bears his family name. “Maybe when someone buys electricity, they don’t care, and the large scale of those companies is an advantage. But when people buy a bottle of wine, they want to know where it comes from, the history, the makers. They want an artisanal product with identity.”

The key will be to communicate those values in simple, memorable ways, including colorful spectacles like the Day of Wine show at the Buenos Aires obelisk last year. On the same November evening, an outdoor theater across the capital hosted folkloric dance performances to promote Mendoza’s annual harvest festival – a lavish celebration staged by provincial authorities every March.

A government eager to help wine producers?

Along with funneling public funds into cultural events, winemakers are calling for state support at higher levels. In November 2017, President Mauricio Macri released a proposal to raise the tax on wine sales from zero to 10%, sending industry leaders into a frenzy. A rush of frantic lobbying ensued, persuading legislators to scrap the idea – a pleasing demonstration of influence for winemakers who are broadly positive about prospects under the current government.

Their laundry list of potential policies that would benefit the industry is comprehensive: From tax rebates on raw materials involved in wine production to improving transport links between Mendoza and Buenos Aires, signing free trade agreements with international partners, like Chile has done, and opening small business credit lines.

“Many family projects are self-financed, so we generate our own investment, and not having access to credit is really hard,” said Federico Sottano of Bodega Aristides, which focuses on quality over quantity. “Our company is small volume and high profit, but we’ve been losing to inflation in the last few years because we didn’t want to increase prices. The cost is that we’ve taken almost no dividends.”

Taming inflation has proven difficult for the Macri administration, with the cumulative total for 2017 clocking in at 24.8%, substantially higher than the official target of 17%, but an improvement on the 2016 rate of about 40%. “If the government does what it has to do, effectively lowering inflation and taxes, it will have an enormous impact on the wine sector,” said Merino.

With the domestic consumption slump unlikely to recover soon, many bodegas are hoping to capitalize on Argentina’s renewed openness under Macri by prioritizing foreign markets. Roughly 20% of national production is exported, which equated to 2.5% (about $817m) of the $32.4bn global export sector in 2016, with Argentina at ninth place in the rankings, marginally ahead of Portugal. Its Andean neighbor, Chile, finished in fourth position with 5.7% of the market, worth nearly $2bn.

The industry is unanimous in the view that Argentina is falling well short of its international potential. But although local consumption is down, there is a clear tendency towards drinking more expensive, high-class bottles – a product range that many insiders believe must be flaunted to the world.

Enter China

In September 2017, a handful of winemakers, including Zuccardi, toasted a significant piece of news: The opening of a virtual Argentine wine shop on China’s Alibaba platform, now the largest online retailer in the world with more than 500m users. “Sometimes, when you have a problem, it’s an opportunity at the same time,” said Zuccardi, referring to the barren harvests of 2016 and 2017. “We’re lucky because the quality of those years was very good and allowed us to launch higher price levels.” Those bottles are ideal for export to China, where new wealthy elites are thirsty for the best blends.

In 2016, the Zuccardi family opened a stunning new bodega in the Uco Valley, 100 km from Mendoza city. Designed more like a Star Wars set than a wine factory, the angular stone building features a shiny dome that reflects the sky and houses a distinctly Masonic tasting chamber.

The $15m Uco project represents a bet on Argentina’s emergence as a star player in the world of wine, with no cost spared in producing distinctive varieties that cannot be replicated. “The more that wines express place, the better they will be,” said Tim Atkin, a London-based Master of Wine who publishes regular reports from across the globe. “Argentines need to believe in themselves, and believe their wines are capable of greatness.”

Visiting bodegas around Mendoza, it’s clear that the spirit of Sarmiento continues inspiring winemakers to innovate in the eternal quest to find exciting flavors. Oenologists aside, the region is full of passionate locals who will help you taste the difference between Bonarda, Cabernet Franc, and Malbec with infectious enthusiasm. If that pride and wisdom is united with a sensible strategy for global growth, focused on emerging markets, Argentine wines may well flourish in the future.

This year’s harvest will be vital as the industry seeks to get back on track. Even during tough times, Zuccardi has remained optimistic. “When you think about a vineyard, it takes five years to start producing, another five to find the right balance,” he explained. “Cycles in the economy and politics are short, especially in Argentina, with so many ups and downs. But we’ve always been thinking long term. There’s no other way to do it.”

Article and podcast published by the emerge85 lab – February/March 2018.