Gun violence can be part of everyday life in Rio de Janeiro, where drug gangs fight over territory and police officers intervene forcefully. Last year, 6,590 people were killed in the city. Frustrated citizens are turning to smartphone apps which help them monitor violent incidents in their neighborhoods in near real-time.

Video broadcast by NBC Left Field on February 6, 2018.

When armoured cars rolled into Brazil’s largest favela in September, furtively followed by hundreds of soldiers, it was just another episode of a long-running drama which plays out across Rio de Janeiro on a daily basis. As a complicated conflict between rival drug trafficking factions erupted into street battles, the army stepped in – with masked, armed men in dark camo uniforms weaving their way through colourful clusters of homes that characterise Rocinha, a famous community in the city’s South Zone.

One of the best-informed people about violence in Rio is Cecilia Olliveira. Between ten and 20 times every day, her smartphone screen lights up with messages she would rather not receive. But they’re not scam emails or Twitter trolls – they’re alerts from Fogo Cruzado, a mobile application that crowdsources information about incidents of violence in Rio de Janeiro and notifies people in real-time.

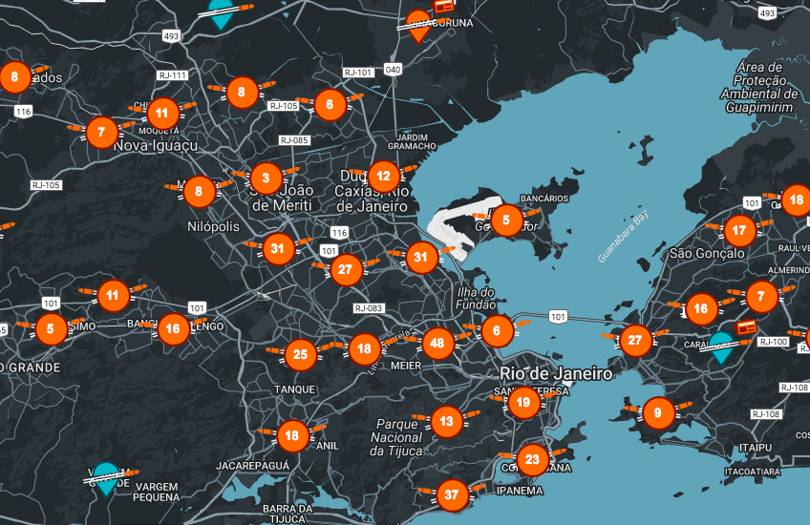

As data manager for the app, Olliveira is responsible for gathering and verifying reports that come in from a network of more than 110,000 users, who can send updates and view an interactive map to check which areas to avoid. As Rio goes through a major public security crisis, Fogo Cruzado – which translates as “crossfire” – is one of the several initiatives that employ technology in innovative ways to increase safety for the city’s residents and their communities.

Since launching in July 2016, with support from Amnesty International, the platform has registered more than 7,500 incidents of weapons fired – with an average 17 per day this year. The situation can vary: Police operations, clashes between rival groups of narco-traffickers, or even petty crime which escalates into armed confrontation. Publically available data shows a total of 1,349 fatalities in Fogo Cruzado’s first year of operation.

When a notification arrives, the app’s algorithms cross-reference the information with specially developed filters and scripts before making it public – on both the interactive map and social networks. User privacy is fundamental, as residents of volatile areas have been known to receive threats for speaking up. Before Fogo Cruzado started collecting data, it was very difficult to get a sense of the scale of the violence.

“People who live in Rio are used to shootings,” Olliveira says. “We talk about them all the time, but we didn’t really have an idea about when, where, or how frequently they happen. Now that information is public. I know people who organise their schedules with the app.”

One of them is Buba Aguiar, 25, a student and community activist who lives in the Acari favela. Like many inhabitants of Rio’s north zone, she tells tragic stories of people who lost their lives because they were in the wrong place, at the wrong time – including a childhood companion who mysteriously disappeared, allegedly at the hands of state forces. Years later, another friend died after being hit by a stray bullet during a telephone conversation with Aguiar herself.

Aguiar checks Fogo Cruzado every time she goes out, whether in the favela or the city centre. “When people see the map and the graphics with the number of incidents, it shocks them,” she says. “It’s a powerful tool for showing the rest of our society what’s happening, especially the elites. But the fact that we have an app with a map of gunshots is actually very strange – and very sad.”

When Brazil won the rights to host the 2014 football World Cup and Rio was awarded the 2016 Olympic Games soon after, hopes were high. With the country enjoying a late-2000s economic boom, many people dared to dream that it was poised to turn a corner – finally taking a seat at the top table of world affairs, banishing a potent inferiority complex that festered from generations of unfulfilled potential.

But as growth stuttered and the economy began to shrink, the two sporting mega-events drained Brazil’s public purse. Rather than inaugurating a prosperous new era, it became a matter of simply getting the job done and praying to avoid logistical disaster. The bankrupt Rio government needed federal bailouts to pay its bills, including police salaries, and crime levels spiked so drastically that 85,000 soldiers were deployed on city streets during the Olympics.

Shortly after the Games were carried off with relative success, the country plunged into a political crisis when left-wing president Dilma Rousseff was impeached and replaced by Michel Temer, a deeply unpopular conservative who is mired in corruption allegations.

More than a year later, the spectre of chaos still floats over Rio. As well as Fogo Cruzado, citizens are calling on other technological tools to try and stay safe. An app called Onde Tem Tiroteio (OTT), which translates as “where shootouts are,” was started by a group of friends who devised a system which checks incoming reports with a network of 7,000 reliable sources on the ground, before alerting users. Since launching in January last year, its Facebook page has gathered more than 400,000 followers.

“For an independent project, it grew more than we could ever imagine,” says one of the founders, Dennis Coli. “We want to make the government look at this issue. They need to do more to protect people.”

The OTT platform has recorded over 4,000 shootouts this year. In addition to the Facebook audience, it reaches more than 100,000 more people via Twitter, the app itself and an open group on Telegram which occasionally distributes disturbing images of prostrate bodies, burning police vehicles or cars scarred with bullet holes.

The ubiquitous WhatsApp messenger is used by countless groups of neighbours to share local updates. In the vast Alemão favela complex, where as many as 120,000 people live, photographer Bruno Itan pays close attention to his phone as he documents daily life in the labyrinth of narrow alleys that wind their way through sprawling hillside settlements.

In late September, when the Brazilian army occupied Rocinha, Itan was on the scene. His photos exploded on social media, capturing the anguished faces of locals watching soldiers sweep through the streets.

“If the government invested in social projects and education, instead of sending the military, it would create citizens who don’t want to enter the drug trade,” says Itan, 29, who also criticized a controversial government “pacification” programme that has achieved mixed results in displacing narco gangs from favelas across Rio since 2008.

Rocinha hit international headlines on October 23, when a Spanish tourist was killed by police on the outskirts of Brazil’s largest favela. The officer who opened fire was soon charged with homicide and placed on desk duty, but official action over police brutality seldom moves so quickly on less high-profile cases – if ever.

Since May last year, a tech project called DefeZap has been giving citizens a path to seek justice against perpetrators of state violence. The idea is simple: Rather than downloading a bespoke application like Fogo Cruzado, users send text reports, photo and video to a special WhatsApp number. A team of investigators at the Meu Rio (My Rio) NGO then analyses the material and works out how to build a legal claim.

So far, about 300 video submissions have been used to initiate more than 140 state investigations. “We manage information independently of government organs and the mass media,” says Guilherme Pimentel, the DefeZap coordinator. He explains that favela residents who may fear approaching the authorities or talking to journalists can now “jump over those institutional filters” without revealing themselves at the initial stage.

“With DefeZap, you can not only film and register things,” Pimentel continues, “but make sure that material reaches the right people,” effectively complementing the data collection carried out by OTT and Fogo Cruzado. “The fact that so many people have smartphones has changed the dynamics of power between citizens and institutions.”

Article published by WIRED on November 12, 2017.

Radio package featured in The Urbanist on Monocle 24 – November 16, 2017.