This year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest boasted a proudly eclectic programme: All-access verité features, hard-hitting investigations, musical explorations and peculiar short films all sat together, at times a little awkwardly, like cramped commuters on the London tube.

This year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest boasted a proudly eclectic programme: All-access verité features, hard-hitting investigations, musical explorations and peculiar short films all sat together, at times a little awkwardly, like cramped commuters on the London tube.

But one of the quirkiest offerings wasn’t even a film, per se – it was a cinematic performance called Nature’s Nickolodeons. Filmmaker/geographer Amy Cutler spliced footage from a huge array of wildlife documentaries, which carefully selected musicians were tasked to “re-animate” by playing live scores composed especially for the occasion.

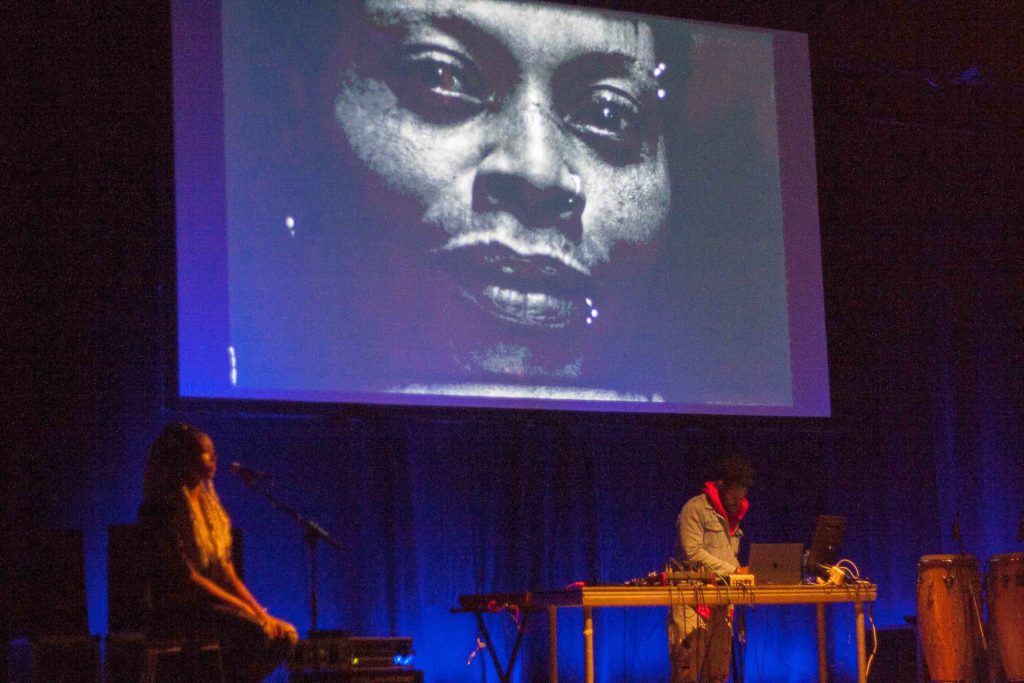

At Sheffield’s Leadmill nightclub, the audience chuckled as beatboxer Jason Singh (above) mimicked the belches of Japanese mudskippers in sync with images projected behind the stage. When the scene shifted to grizzly hoards of rats swarming over the large screen, rodent squeaks and scratches rose up from all around us; a “feral choir” led by Phil Minton had infiltrated the crowd to provide an old-school surround sound experience.

Cutler’s inspiration for the piece, which contained six different sections, came from Walt Disney’s abandoned plan to present nature documentaries in zoos – fused with her desire to explore how blockbuster TV shows like Planet Earth play on our emotions to weave spellbinding stories. “From the titillating and the trashy, to the tug on the heart-strings, it’s hard to think of a format which revolves more around the manipulation of audience appeal,” explained Cutler.

“Why is it so important to intervene in the idea of the nature documentary – often the most passively consumed form of nature narrative – and draw attention back to its social life as, first and foremost, a live experience?”

For many protagonists of live cinema – not limited to nature docs – the answer is a pressing economic need to devise new, exciting incentives that attract people to independent film venues in the age of Netflix.

Purists will argue there’s nothing quite like the hallowed magic and grandeur of a real cinema – but high-quality streaming on demand, combined with increasingly affordable home entertainment systems, presents a more comfortable, convenient alternative for the digital generation.

At Sheffield Doc/Fest, Nature’s Nickolodeons was part of a broader live programme. As well as simultaneous soundtrack performances, including a composition by Gaika for New York photographer Khalik Alah’s mesmerising Black Mother art-doc hybrid (below), several films were followed by concerts – such as Tranny Fag, which tells the story of enigmatic Brazilian trans singer Linn Da Quebrada, who seemingly teleported out of the screen from São Paulo to play for a raucous crowd at the Abbeydale Picture House.

“This was a year for live cinema – to show people where we want to take the festival,” said Luke Moody, chief programmer at Sheffield. “Commercial venues don’t have the ability to experiment and take risks, so what we do is try things out and prove to exhibitors that these ideas can work.”

And Moody isn’t overly concerned by the Netflix effect. “We’re ridiculously spoiled, because you can find anything online, but people are hungry for alternatives,” he explained. “The beauty of any event is the experience of being with other people – bodies vibrating with emotion, heads nodding to music. It’s that hum of movement.”

The doc festival even held a Live Cinema Summit, for the first time – convened by its eponymous parent organisation, Live Cinema UK, which also collaborates with artists and produces industry studies.

A 2016 report found that 48 percent of 576 independent film exhibitors (excluding multiplexes) hosted live events, broadly defined as “film screenings augmented by synchronous live performance, site-specific locations, technological intervention, social media engagement, and all manner of simultaneous interactive moments including singing, dancing, eating, drinking and smelling.” More than half of those events involved soundtrack performance.

The act of setting up a cultural body to effectively institutionalise the live cinema sector is a fascinating development: As well as providing financial support, exploring distribution channels and conducting research, it enables curators and practitioners of hybrid forms, which often defy clear categorisation, to gather around their own flag – and that’s exactly what happened at the Sheffield summit.

For cross-disciplinary creators, having a market-friendly label to stick on the porous grey area between cinema, music, theatre and visual art – as well as an organisation to actively nourish that intriguing intersection of the cultural landscape – is a compelling idea.

“Although more people have started appreciating and understanding it over the last 10-15 years, it still falls between these cracks in terms of established cultural spaces,” said Christopher Thomas Allen, an audiovisual artist who has been working on live AV since the 1990s with his Light Surgeons collective.

“There’s an expectation of visual accompaniment to lots of music,” he continued, “so music video and video have become a kind of everyday vocabulary; people are creating their own media. Live cinema has so many tentacles, which makes it interesting – but also hard for people to define.”

Three years ago, Allen was a founder of London’s Splice festival (above). In contrast to the film focus at Sheffield, it champions another key player in audiovisual performance: The “VJ” – simple shorthand for the visual equivalent of a DJ. Generally speaking, a VJ’s role is to produce images which closely follow the sounds of a band, solo artist or selector in real time – and increasingly conceived in tandem with the music itself.

It’s a discipline that has rapidly grown in recognition, as the very existence of Splice can attest. En masse, major venues and festivals have installed powerful projectors or giant LED screens, which multiply performance possibilities – and some promoters are starting to give VJs equal billing as their musical counterparts. In South America, ZZK Records actually signed a digital artist – Fidel Eljuri – who tours globally with his fellow Ecuadorian label-mate, Nicola Cruz, a darling of the electro-folk scene.

Closer to home, the pan-European AVNode network has become a vital nexus for the audiovisual community, using EU funds to support 36 festivals across a dozen countries, including Splice. Another is Rome’s Live Cinema Festival, which in 2016 and 2017 took place at the MACRO museum – a venue that symbolised the increasing acceptance of live AV in the institutional realm of contemporary art.

“For many years, it was mainly happening at underground parties and raves, but now we’re stepping out of the shadows,” Hungarian VJ Gabor Kitzinger told me at the 2016 Rome event. He identified a tipping point as somewhere around 2008, when video mapping of buildings started to gain exposure – pushing a dynamic visual subculture into the public eye.

Diehard live music fans with a cynical disposition might argue that VJs merely compensate for a lack of spectacle on stage during electronic gigs, where computers are usually the main instrument. At some concerts, the union between audio and visual can feel slightly precarious – but the most advanced proponents are deeply integrating cinematic storytelling into the performative medium.

At this year’s edition of Splice, composer Matthew Herbert collaborated with Christopher Thomas Allen and others (above) to premiere a piece crafted from sounds and images of a mechanic systematically dismantling a Ford Fiesta. As twisting pistons and clunking hammers were knitted into a dystopian sonic panorama, with Byron Wallen’s eerie trumpet floating over the chaos and glitchy visuals on screen, it was easy to read the artist’s intention: A scathing metaphor for Brexit.

In 2016, Herbert produced a site-specific work for Ron Arad’s “Curtain Call” immersive cinema installation at London’s Roundhouse; it featured an electronic symphony of sounds made by a naked body over 24 hours, coupled with abstract corporeal visuals beamed onto a 360-degree permeable screen comprised of 5,600 silicon cables.

The United Visual Artists studio has designed AV concepts for major musical acts such as Massive Attack, whose live show features LED displays which gather data in real time, mapping it into a vivid visual matrix which invites audiences to contemplate privacy, censorship and human rights. UVA also collaborated with pop singer James Blake to create an interactive stage show with light patterns and images triggered by musicians in his band.

Looking further back, Steve Reich is another contemporary musician who has pushed boundaries with projects like his video-opera Three Tales (2002), a collaboration with filmmaker Beryl Korot. In the opening “Hindenberg” movement, text from news articles is remixed into a chilling choral score, accompanied by harrowing images of the namesake airship going down in flames in 1937. And the final “Dolly” section explores animal cloning by spinning scientist soundbites into a polyphonic audiovisual patchwork which tells the story of that famous sheep.

That cosmic synthesis of producing a film and its music together in a unified, organic creative process may be the panacea for live cinema as an art form. It goes beyond the idea of simply inviting a composer to write a soundtrack, or adding a live score to a silent film – which was, of course, the original incarnation of live cinema in the early 20th century.

The notion of creating experiential events around film actually goes back to the 1950s and ‘60s, when the term “expanded cinema” was coined by experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek – an associate of avant garde icons like John Cage and Merce Cunningham. The trio collaborated on Variations V (1966), which featured multi-screen projections accompanying dance movements that triggered sound sensors manipulated by musicians.

Other notable artists connected with that pioneering crossover field include Nam June Paik, Joan Jonas and Phill Niblock – whose Experimental Intermedia foundation is named with a term commonly used to describe audiovisual work in the institutional ecosystem of museums and galleries.

Is that kind of formal language and structure necessary to validate an art form? Certainly not – but it often happens anyway. The fundamental difference between the expanded cinema era and today is technology: Just as it challenges the film business with Netflix and plasma screens, the accessibility of creative tools and digital distribution has levelled the playing field in numerous ways.

“People are reclaiming the means of production, rather than it all being mediated by big institutions and corporations, which are hugely slow and guarded,” said Christopher Thomas Allen. “Now you can buy a powerful projector, build your own screen, illuminate a building with video mapping. Film has escaped the cinema.”

Arguably, the internet has cracked open institutional gates by removing key economic and physical barriers to discovering (or releasing) work; it’s never been easier to see, or to be seen. And, as stronger ties gradually develop between the fine art establishment, the independent audiovisual realm and the traditional film industry, this is an exciting moment of convergence for the world of live cinema.

Published by The Quietus – August 11, 2018.

Reposted at Vantage – August 21, 2018.

All photos – courtesy of Sheffield Doc/Fest and Splice festival.